Despite the cognitive dissonance produced by the visual contrast between yoga, bodybuilding, and martial arts, these seemingly disparate domains of practice are intimately linked on a number of different levels. The invention of postural yoga in late nineteenth- and early twentiethcentury India is directly linked to the reinvention of sport in the context of colonial modernity and also to the increasing use of physical fitness in schools, gymnasiums, clinics, and public institutions.

Prior to the early nineteenth century, yoga was understood as a practice that focused on the acquisition of power, which involved the manipulation of supernatural and natural elements, both physical and ecological, gross and subtle. As such, metaphysical mysticism and meditation, while important, were always grounded in the more encompassing and complicated problem of materialism. Given that yoga is now conceptualized in terms of balanced holistic health, spirituality, and esoteric mysticism, it is important to appreciate the extent to which a range of premodern and early modern practices were focused on radical embodied ideals of physical and metaphysical self-transformation.

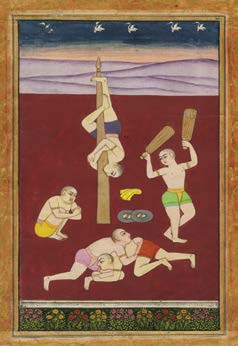

Five Athletes, symbolizing a musical mode (Deshakha

raga). India, Deccan plateau, ca. 1880–1900. Opaque

watercolor on paper, 28.3 × 8.5 cm. Asian Art

Museum of San Francisco, B 87D19

Sri Tirumala i Krishnamacharya (1888-1989), is often regarded as the father of modern yoga, largely due to the profound influence two of his disciples – BKS Iyengar and K Pattabhi Jois – have had on contemporary practice all over the world. But like his pioneering contemporaries in western India, Krishnamacharya was strongly influenced by gymnastic physical culture, organised athletics, and the nature cure, especially after he was recruited by the maharaja of Mysore in the early 1930s to teach and provide physical education training. With royal patronage, he established a gymnasium for yoga training that emphasised physical strength, stamina, and muscle tone. Along with many Indian physical culturists of the time, such as Kodi Ramamurty Naidu and Bhishnu Charan Ghosh, Krishnamacharya put on demonstrations of physical prowess that blurred the line between natural and supernatural power, for example, stopping both his pulse and moving cars as well as lifting heavy objects while performing difficult asanas. Physical strength and stamina notwithstanding, Krishnamacharya focused his training on postural movement and pranayama, which finds dynamic expression in the form of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga developed by Jois.

T. Krishnamacharya Asanas. India, Mysore, 1938. Sponsored by Maharaja Krishnaraja Wodiyar. Digital copy of a lost black-and-white film, 57 min. Courtesy of Dan McGuir e

In light of the history of modern postural yoga in India, it is clear that Jois’s and Iyengar’s success on the global stage was, in part, a result of their focus on adept athletic asana gymnastic performance, whereas Swami Kuvalayananda (18831966), Sri Yogendra, and others, such as Selvarajan Yesudian (1916-1998) highlighted how physical education and fitness were institutionalized. All, however, worked within the same rubric of athleticism, physical culture, and muscular Christianity even though there is a tendency to forget this and represent modern movements as the perfect reflection of what looks like an ancient tradition. It is relatively easy to perform a difficult asana and make it look as though it is both supernatural and mystically archaic but more challenging to make it fit explicitly into the rubric of modernity and modern physiology.

Here, the case of Bishnu Charan Ghosh (1903-1970) is important. Ghosh, the younger brother of Swami Yogananda, was directly involved in the development of Yogoda physical fitness as an integral component of the Self-Realisation Fellowship, both in India and the United States. Yogoda was a hybrid form of postural practice similar to Yogendra’s rhythmic exercises and Kuvalayananda’s mass-drill asana programme, but was intended for school curricula. In 1930, Ghosh established Ghosh’s College of Yoga and Physical Cultural in Calcutta and began to experiment with bodybuilding exercises combined with asana. As documented in Barbell Exercise and Muscle Control, Ghosh achieved significant physical development and muscular definition, clearly establishing himself as a bodybuilder in the mold of British muscle man Eugene Sandow (1867-1925) and a spectrum of other bodybuilders in India, such as Professor KV Iyer, Professor J Chandrashekhar, Swami Shivanand Teerth, Manotosh Roy, Ramesh Balsekar, Chit Tun and the iconic Monohar Aich, who started his career as a strong man in PC Sorcar’s travelling magic show. Ghosh modified asana routines to produce muscle definition and control, including the articulation of abdominal recti, which is distinctive of nauli kriya (one of the shatkarma cleansing procedures that involves isolating and rotating the abdominal recti muscles). His legacy is most clearly visible in his most famous student, Bikram Choudhury, who was a bodybuilder and weightlifting champion in India before the global success of Bikram Yoga put him in the international spotlight, placing emphasis on the athletic body in a way that brought asana directly back into focus and linked it to muscle control.

With this in mind, one can better appreciate the significance of Dr Shanti Prakash Atreya’s (1917-1990) perspective on yoga and the way in which the martial art of wrestling fits into the history of modern Indian postural practice. What Atreya – a yoga philosopher and wrestling champion – does in essence, is invert the logic of Kuvalayananda and Yogendra’s innovation as well as Krishnamacharya’s synthesis of asana and gymnastics, making the argument that wrestling is yoga with a slight twist and that the body of the wrestler reflects the material essence of yogic power. His perception of how this power is embodied in the material essence of ojas and semen is thus “inside out” relative to Ghosh’s “outside in” perspective on bodybuilding and muscle control.

Atreya himself sought to embody his theory of yogic wrestling and did so quite successfully, both in terms of athletic success in tournaments and by becoming one of the most articulate, authoritative, and respected voices in the arena of nationalistic rhetoric concerning the development of nonviolent, muscular, moral masculinity. From the mid-1960s until his death in 1990 he published extensively, primarily in a specialised magazine dedicated to the promotion of wrestling in India.

In many ways Atreya’s argument is that wrestling is more “yogic” than various forms of modern postural yoga that place emphasis on the gross features of muscle control, flexibility, and physical fitness. In any case, his argument is perfectly consistent with a history of many perceptive innovations, extending from Patanjali through to Bikram, and highlights the way in which yoga in modern India must be understood with a clear perspective on the material nature of metaphysical fitness.

For the full article, please refer to Yoga: The Art of Transformation [link to: http:// asia.si.edu/support/yoga/cataloguepreview.asp], edited by Debra Diamond. Copyright 2013, Arthur M Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved.

Other

Other